"The definition of a monad M is like that of a monoid in sets, The set M of elements of the monoid is replaced by the endofunctor T: X -> X, while the cartesian product × of two sets is replaced by composite of two functors" - Saunders Mac Lane, Categories for the Working Mathematician pp138.

ExampleA monad is an important concept in mathematics. It is a pattern that occurs in many branches of mathematics. To take just one example, in vector spaces, imagine that we want to calculate the result of doing a sequence of finite rotations of a solid body in 3D space. Each finite rotation is an endofunction from vector space to itself and the results of any sequences of rotations can be calculated using two functions: an algebra which represents the 3D transformations as elements (such as matrix or quaternion) and combines them using multiplication and a function that calculates the movement of points given any 3D transformation. |

In general a monad can relate an algebraic theory to function composition.

It also has applications outside mathematics. In computing, for instance in the language Haskell, a monad can convert imperative code into pure functional code.

The power of this monad concept is not always apparent (to me at least) from the definition so, after giving the technical definition, we will look at various ways to approach this topic to get a more intuitive understanding.

Technical Definition

The above definition about a monad being a monoid in the category of endofunctors can be expressed in terms of natural transformations as follows:

A monad T = <T,η,µ> on a category C consists of

Natural transformations are explained on this page. |

|

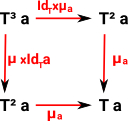

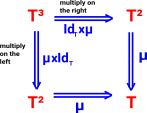

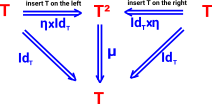

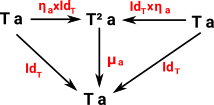

These natural transformations must obey the following axioms, that is the following diagrams must commute:

| associative square: | unit triangles: | |

|

|

|

| The associative square says that we can multiply on the right first (IdT×µ) or on the left first (µ×IdT) and the result is the same. | The unit triangles say that we can insert the unit on the right first (IdT×η) or on the left first (η×IdT) and in each case when we multiply we get back to where we started.. | |

Note that in these diagrams:

|

||

Endofunctor

A functor from a category to itself is called an endofunctor.

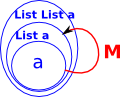

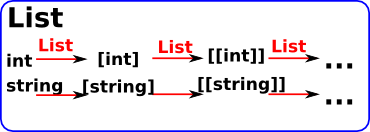

This is often defined recursively, for example, we can define a functor from List to List which allows one list inside another list.

So, for example, the endofunctor for a list monad generates a sequence of objects:

|

|

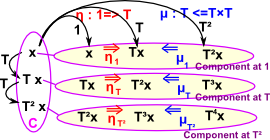

Monad in terms of Components

When working with monads, especially if we are modeling them in a computer program, it can be complex to model natural transformations with a form like:

(x -> y) -> (z -> w) so it can be more practical to model in terms of the components at 'a'.

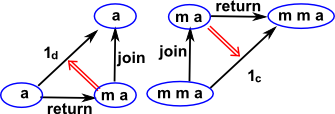

In the above diagrams points represent functors and arrows represent natural transformations. However we can go back to more conventional diagrams by taking the component at 'a'. This means that:

- The endofunctor becomes a sequence of types.

- The natural transformations becomes functors between these types.

The axioms become:

|

|

Note that:

- µa is the component of µ at a

- ηa is the component of η at a

- x applies the two functors in parallel.

The functors become the nodes of the diagram and the natural transformations become the arrows.

Ways to think about Monads

It seems to me that any really powerful idea in mathematics has many ways to approach it and we only feel that we have an intuitive understanding of the concept when we can understand several of these approaches. We could look a monads as:

- An endofunctor with two natural transformations obeying certain rules.

- An adjunction viewed from one end.

- A monoid whose elements are functors.

- A way to generate a category of algebras from function composition in an endofunctor.

- A way of joining together individual computations.

- A way of encapsulating computations.

- A way of building up an algebraic data structure.

- A way to embed an imperative program in a pure functional program.

We will look at each of these in more detail later.

First lets look at how the concept can be built up from the concept of an endofunction.

Monad from Endofunction

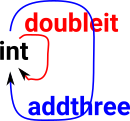

| An endofunction is a function whose codomain is equal to its domain. That is a function from a type to the same type. |  |

For example:

•doubleIt(int a):int = 2*a •addthree(int a):int = a+3

These functions both have type int->int, that is: they are endofunctors.

One advantage of this is that we can chain together a sequence of such functions, effectively allowing us to compose fragments of computation in many ways.

Natural Transformations

The above endofunctor can be made even more powerful by adding two 'natural transformations'. These are mappings between the endofunctors.

So, in the above example:

- the endofunctor has type int->int

- so the natural transformations have type: (int->int)->(int->int)

Multiplication

The first natural transformation that we want to add is called 'multiplication' (although this does not correspond to the multiplication of the underlying type 'int').

Imagine that we enhance the above endofunctor by adding the following:

doubleItandaddthree(int a):int = 2*a+3

We now have a relationship within the endofunctor

doubleItandaddthree = doubleIt • addthree

where: • means do the left hand side first then do the right hand side.

This has type: (int->int) • (int->int) -> (int->int)

but we can Curry '•' into '->' .

So we have a new operation called 'multiplication' although it has different properties from the multiplication of the underlying type 'int'.

Unit

We also want to add a second natural transformation which introduces this function:

donothing(int a):int = a

That is a function that does nothing (it maps 1 to 1 and 2 to 2 and so on) but that has a signature of: int->int so it is not a natural transformation.

'Unit' is a natural transformation with signature:

()->(int->int)

That is it introduces our donothing function from something without any parameters.

Again, this 'unit' natural transformation is not the same as the identity element of either of the operations of the underlying 'int' type.

Monad

So, in the above example, we have used endofunctors to introduce a completely new algebra from a known one (int).

Programming Issues

Here the functors seem to represent the fixed structure (compile time) and the natural transformations seem to represent the dynamic structure (run time).

More Complicated Monads

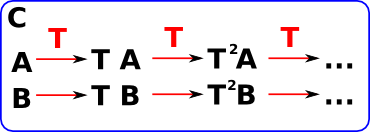

The examples that we have given so far are a simple type of monad where the endofunctor takes us back to exactly the same type (which is what we expect with an endofunction). Now we consider a more general monad where the endofunctor maps, not back to the same type, but to a different (but related) type.

So here we are generalising the situation by lifting up from endofunctions to endofunctors.

List Example

A simple example of this is 'List' (at least programmers call it 'list', mathematicians may call it 'word') which is a functor which maps:

- int to List int

- string to List string

- and so on

Applying the functor twice would map int to List List int, that is, a list of lists. The multiplication µ can, for instance, be 'flatten' which just removes the inner brackets, that is, it flattens the structure.

Generalising

| It is not necessary to stay with the situation where our composed functions map from a type back to the same type. |  |

| We can instead have a whole sequence of types formed by an endofunctor. We still have an infinitely composible sequence but each type in the sequence is a different type. |  |

An example of this is the 'list' monad: |

|

Monad in Terms of Sets

As when we started looking at category theory, on this page, we can start looking at the concept of monads in terms of sets and then generalise to categories.

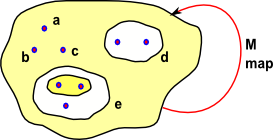

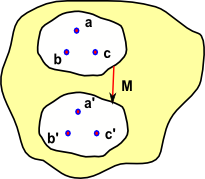

|

We start with a set which contains elements such as a,b & c, it may also contain subsets which themselves consist of elements like these and subsets of subsets and so on. |

|

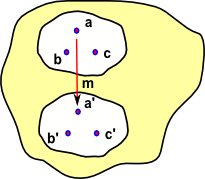

Imagine that we have some mapping 'm' that maps say a->a' (or in a different notation a -> m a) |

|

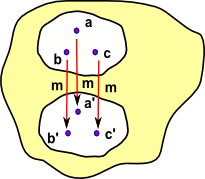

Now imagine that b and c are also compatible with this mapping so we can add similar maps b->b' and c->c' and so on. |

|

It would be useful to be able to avoid the need to iterate over the elements and map them individually. We can map the whole set as a complete object provided that: M {a,b,c} = {m a,m b,m c} Usually in mathematical terminology we don't make a distinction between M and m, we use the same symbol regardless of whether we are mapping elements or whole subsets. |

|

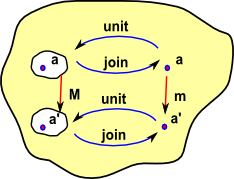

We can add two functions:

So 'unit' and 'join' are inverses. |

|

In the same way that we can use 'M' to map elements or whole sets we can use 'unit' and 'join' to map elements, sets or mappings. So here 'unit' and 'join' represent mappings of mappings. In fact they are natural transformations. |

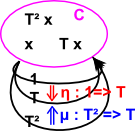

In Terms of Components

| Above I tried to draw the monad to show the endofunctor external to C. We might get a clearer impression if we draw the components like this: |  |

So C is a category with components (objects or, if C is a set, elements) such as x.

|

|

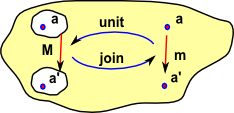

The two natural transformations are:

name: |

symbol: |

|

| unit | η: 1 -> T |

where η is the lower case greek letter: Eta |

| multiplication or join | µ: T² -> T |

where µ is the lower case greek letter: Mu |

When programming in Haskell µ is called 'join' instead of 'multiplication'.

Note that, in some cases η is the inverse of µ, although it only goes from higher powers to T, it does not go back to 1.

Monads and Algebras

| This is explained on this page. |  |

Examples of Monad

Vector Space: {formal -linear combinations ∑ λi vi }->V -linear combinations ∑ λi vi }->V(explaned on this page) |

|

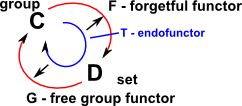

- Group: {words in G}->G

- i.e. presentation of a group

|

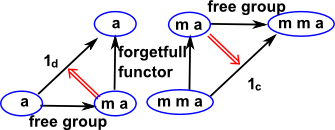

In this example F is the forgetful functor which removes the structure from a group and makes it into a set, G adds structure to a set to make it into a free group. |

x

| Example | category C and its endofunctor |

Kleisli | Eilenberg-Moore |

|---|---|---|---|

monoid |

|

|

objects: succ arrows: succ->succ |

finite group (see Saunders Mac Lane 2nd ed p141) |

|

||

vector space (see this page) |

product combines transformations such as rotation | ||

list µ = flatten |

objects: X,TX,TTX... arrows: T |

objects: X,TX,TTX... arrows: X->T X |

objects: T applying µ gives: T -> T |

| program | |||

cat on set |

|||

Applications of Monad for Programming

In a purely functional computer language such as Haskell, the result of calling a function must depend only on the function called and its parameters (as a mathematical function does) the result must not depend on anything external such as input/output (IO) or some variable or system state. In practice this is too limiting as a computer program would not be much use without Input/Output and passing a system state into lots of function calls seems very tedious. A monad allows us to do these things, to some extent, while most of the program still has the benefits of being purely functional.

A part of an imperative (non-functional) program might look like this:

int x,y,z; x = funct1(1,2); y = funct2(x); z = funct3(x,y,5); x = funct4(y); |

where x,y and z are variables which can change their value. In a purely functional program, variables can't change like this and so we need to do everything by functional composition like this:

funct3(funct1(1,2),funct2(funct1(1,2)),5); |

Not exactly readable, to try to make it easier to work with function composition Haskell defines the following typeclass:

class Monad m where

(>>=) :: m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

(>>) :: m a -> m b -> m b

return :: a -> m a

fail :: String -> m a

Where 'm' is a type constructor, that is 'm a' takes a given type and returns another type.

If 'm' were [] that is List and 'a' were char then 'm a' would be [char] a list of characters. This could be applied recursively so 'm m a' would be [[char]].

If 'm' were * -> * that is a function and 'a' were char then 'm a' would be 'char -> char' a function from character to character. This could be applied recursively so 'm m a' would be:

(char -> char) -> (char ->char).

So how is this related to the mathematical concept of monads discussed above? It may help if we replace '>>=' with a related function 'join' as follows:

join :: (Monad m) => m (m a) -> m a join x = x >>= id

Where 'id' is the identity function:

id :: a -> a id x = x

So now: return join maps type: So map and join are our natural transformations. |

|

Monad and Monoid

For me, so far, the explanation that comes closest to tie together monads in category theory and monads in Haskell is that monads are a monid whose objects have the type a->m b. I can see that these objects are very close to an endofunctor and so the composition of such functions are related to an imperative sequence of program statements. Also functions which return IO functions are valid in pure functional code until the inner function is called from outside.

This id element is 'a -> m a' which fits in very well but the multiplication element is function composition which should be:

(>=>) :: Monad m => (a -> m b) -> (b -> m c) -> (a -> m c)

This is not quite function composition, but close enough (I think to get true function composition we need a complementary function which turns m b back into a, then we get function composition if we apply these in pairs?), I'm not quite sure how to get from that to this:

(>>=) :: Monad m => m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

Monad and Adjunction

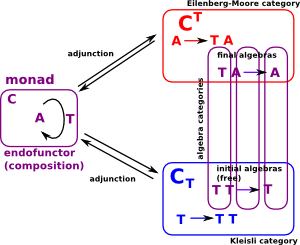

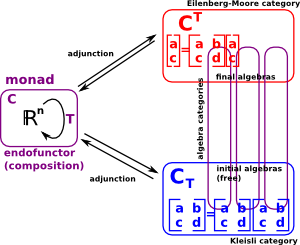

Every monad arises from some adjunction, in fact typically from many adjunctions. Two constructions, the Kleisli category and the category of Eilenberg-Moore algebras, are extremal solutions of the problem of constructing an adjunction that gives rise to a given monad.

The example about free groups can be generalized to any type of algebra in the sense of a variety of algebras in universal algebra. Thus, every such type of algebra gives rise to a monad on the category of sets. Importantly, the algebra type can be recovered from the monad (as the category of Eilenberg-Moore algebras), so monads can also be seen as generalizing universal algebras. Even more generally, any adjunction is said to be monadic (or tripleable) if it shares this property of being (equivalent to) the Eilenberg-Moore category of its associated monad. Consequently Beck's monadicity theorem, which gives a criterion for monadicity, can be used to show that an arbitrary adjunction can be treated as a category of algebras in this way.

Example

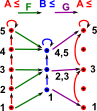

On the adjunction page (see example 1 here) we looked at an example using a preodered set (illustrated using a directed graph). So, can we turn this into a monad?

|

Here is F (shown on the left) and G (shown on the right). |

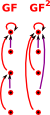

|

So GF and GF2 are as shown here. |

The Kleisli Category of a Monad

I would like to link together all the different category theory explanations: endofunctor+2 natural transformations, Kleisli category, a monoid whose objects are monoids and so on. For me the thing that seems to link all these explanations is that they are two level. That is, normally we treat category objects as black-boxes where we imply their properties from their outside interactions, but here there seems to be a need to go one level inside the objects to see what's going on? We can explain monads without this but only if we accept apparently arbitrary constructions.

Monad using String Diagrams

more about string diagrams on this page

Because there is only one object, it is not shown on the string diagram. So, in this case, crossing over the line means going once round the endofunctor 'T'.

| Category Diagram | String Diagram | |

|---|---|---|

| A monoid is an endofunctor with two natural transformations and axioms shown below. | ||

| The first natural transformation μ | ||

| The other natural transformation η | ||

| The left unit triangle | ||

| The right unit triangle | ||

| The associatively square. |