Equality of Types

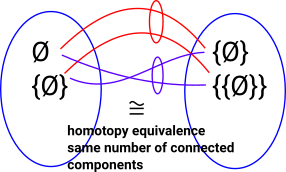

On the page here we looked at a type theory approach to equalities between types.

Here we look at a different approach based on the ideas of Vladimir Voevodsky and others. These ideas bring together theories from homotopy and from type theory.

In this theory there are multiple ways that types can be equal. As an alterative to treating isomorphism and equivalence in the usual way we can treat them as being equal in multiple ways.

Equality and Groupoids

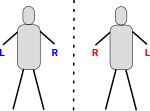

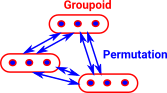

Lets start with a group and compare a group expressed as a permutation group or as a symmetry group. Perhaps the simplest example might be mirror symmetry.

Imagine we can see two perfectly symmetrical images, one reflected in a mirror and the other one directly. There are two ways we could define the images to be equal. We could say they are equal if they look the same, in which case we can say that the reflected image is equal to the non-reflected image. Or, if we have some more precise way to determine left and right, an image will be equal to itself but not its reflection. |

|

| Another way to represent such a group is as a set of permutations. |

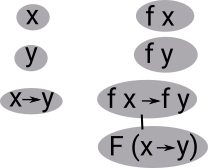

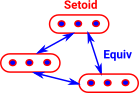

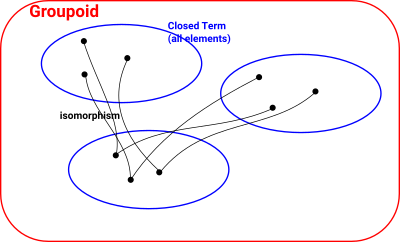

In order to represent, more generally, the structure from multiple equality definitions we need to generalise from groups to groupoids.

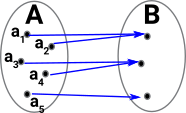

| Here we have 2 sets. They are not equal because the elements are labeled differently. However they are isomorphic (essentially the same). Here we look at this isomorphism in a different way, as multiple ways they can be equal. | |

| One way they can be equal is if a=c and b=d. | |

| Another way they can be equal is if a=d and b=c. |

So, for pure sets without any additional structure, if they have the same number of elements then the number of ways they can be equal is equal to the number of permutations (in this case 2).

This structure where we have permutations between different elements is called a groupoid, more info on the page here.

If the sets have additional structure then we may need higher order groupoids where there are equalities between the permutations. See Wiki.

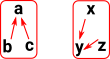

| For example, if we have a partial order, the arrows between nodes can also permute as long as they permute in a consistent way with the nodes. In this example we might not want 2 arrows out of a node to be equal to 2 arrows into a node. |  |

| If we have multiple arrows between the same nodes we can permute them independently of the node permutations. |  |

Oidification

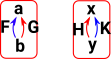

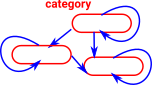

Oidification allows us to start with a single object and one (or more) arrows back to itself and generalise this to multiple objects. This new structure does not need to have arrows between every pair of objects but composition always exists and every object has an identity arrow.

Here the words 'object' and 'arrow' are used in the category theory sense as described on the page here.

Here are some examples:

| Single Object | Multiple Objects | |

|---|---|---|

|

This imposes an external equivalence relation and internalises it. |

An example would be a set with a set with a fixed number of elements. |

Since the arrows are reflexive, symmetric and transitive this gives an equivalence relation. |

|

This can be thought of as a weakening of a setiod. Instead of equivalences we have isomorphisms, that is the permutations show how objects are equal in multiple ways. |

|

|

|

Just to confuse things the naming conventions have changed here. Monoid has an 'oid' but this is the single object case. A Monoidoid is a category. |

|

|

Equality - Sets (h-level 2)

In set we can make a proposition of equality between any two elements. A proposition may be true or false/unproven.

| Extensional Type Theory | Cubical Type Theory |

|---|---|

In a language such as Idris, propositions are types and because there is only one way for it to be true we can use a relatively simple notation. a=b |

In cubical type theory a proposition is represented as a path between the two elements. Path A a b |

| More about proofs in Idris on this page. | More about proofs in cubical type theory on this page. |

So far we have only created a proposition type. To prove it true we need to create an instance of that type. In set, elements are only equal when they are the same element. Propositions involving variables such as x=x+0 are more interesting.

| Extensional Type Theory | Cubical Type Theory |

|---|---|

In this case we have a single constructor since there is only one way to construct it. Refl : a=b |

In this case we need a path out of the interval. <i> x : Path A a b |

So set is like a collection of points, we can now go on to add some higher level structure.

Equality - Groupoids (h-level 3)

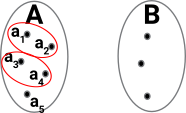

Here we start with set , as above, but we add an equivalence class. We can do that by defining an external equality or it also arises when we have a surjective function out of the set, when we reverse this we get a fibration.

We now have two types of equality and there are different options for dealing with this. We could collapse equal elements to a point (like with quotient) which would give back the set or we could keep the two types of 'equality' which can be internalised to form a setoid or groupoid.

So this is related to and brings together various mathematical structures. See these pages for details:

Simple Example

| Start with a set. Here the only equalities are that each element is equal to itself. | ||

| What if we add additional equalities, say a=c and b=d, these are like external equalities imposed on the set. There are various ways we could do this. | ||

| We could treat all equalities the same in which case 'a' and 'c' become the same element. The set can contract on chosen elements. | ||

| Or we could keep the equalities separate. This gives us a setoid structure. | ||

| We could think of this as a fibre structure. |

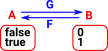

Comparing Whole Sets

Lets take a very simple example, comparing two element sets, one set has the elements 'true' and 'false' and the other set has the elements '0' and '1'. One approach, which we might call 'extensional equality', is to say that two sets are equal if they contain exactly the same elements. In this case the elements are different so, these sets are not extensionally equal. |

|

A different way to define 'equality' between these sets is 'isomorphism'. They are isomorphic if we can construct arrows in each direction that allow us to get back to where we started: IdA = G•F By this measure these two sets would be isomorphic. For more information see category theory pages here. |

|

Univalence Axiom

We now introduce Voevodsky's 'univalence axiom' (A=B)![]() (A

(A![]() B). (identity is equivalent to equivalence).

B). (identity is equivalent to equivalence).

Here equivalence is like isomorphism. So the 'univalence axiom' seems like nonsense because, as defined above isomorphism and equality are different.

One way to interpret this might be that isomorphism is equality in multiple ways.

| For instance, in our example, if we set: 0 = false 1 = true then the sets are equal. |

|

| Alternatively if we set: 0 = true 1 = false then the sets are equal in a different way. |

For more information about this 'equality' between Boolean (two element sets) and how these ideas can be extended to other types see the page here.

Homotopy and Type Theory

The structure described above can be related to homotopy theory.

| Type Theory | Homotopy Theory |

|---|---|

A type |

A space |

Homotopy theory is discussed on the page here.

Type Theories

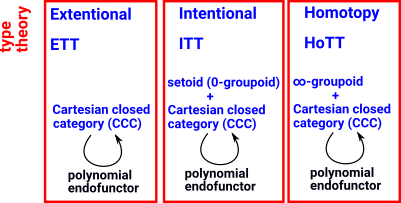

There are various type theories including:

The difference between these is the relationship between equalities such as extensional equality and intentional equality. |

|

Homotopy Types

In this section we just think about how mathematical structures could be related to topology and homotopy. These models may not work for higher order paths (coherence problem) so more indirect models have been developed (see cubical types page).

So this is just for intuition.

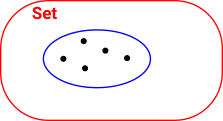

A set is just a discrete topology. Here is a set with 5 terms. So set theory is part of HoTT. |

|

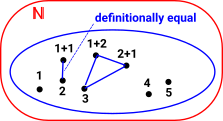

Natural numbers (with addition) have additional structure. So in addition to the terms, represented by points, we now have lines linking things which are equal. I'm not sure this diagram fully shows the shape of natural numbers? Does it show the '1' in '1+1' is the same as the point 1. |

|

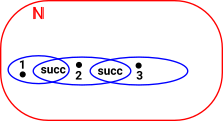

| Could we instead characterise the topology as open sets for the numbers (0 dimensional points) linked by 1 dimensional lines which is the successor function. |  |

Univalence Axiom

Properties

There is an idea that, if A and B are isomorphic, then A and B should have the same properties.

So if 'A' is some structure then ' φ(A)' is a statement in first order logic about A.

If two things are isomorphic then all properties of A are also true of B:

A![]() B -> P(A) <=> P(B)

B -> P(A) <=> P(B)![]() P

P

Some properties, such as: 'contains empty set', don't obey this principle. So set theory violates this. The properties we want are invariant properties.

In Homotopy Type Theory (HoTT) these invariant properties are homotopy invariant properties such as:

|

|

Mathematicians want to find a foundation for mathematics that satisfies this principle.

This would make it easier to compute mathematics (automate proof checking and so on). Set theory axiomisation (formal set theory) is hard to work with because:

- Has properties which are not invariant.

- Requires arbitrary choices

- Axioms don't tell you how to construct structure - It would be better to have formal system in some constructive system of mathematics (to prove something we construct it).

- Set theory is built on top of logic.

Mathematicians that have worked on this problem:

- Lawvere

- McLarty

- Makkai

- Voevodski

Voevodski approach is to formalise all of maths as homotopy types (everything is a shape).

H-Levels

(see Dimitrios Tsementzis - Youtube)

| H | invariant | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 2-cat | 3D hole | |

| 3 | category theory | equalities can be equal

|

2D hole |

| 2 | set | Can be equal in many ways | path connected components |

| 1 | point |

Intuitional logic Can be equal in one way |

|

| 0 | point |

A set in homotopy is a discrete space (so set theory is contained in homotopy theory)

Example

| Imagine we have 2 sets, A and B, which are equivalent. |  |

This induces 'equivalence classes'. So the equivalence of two sets: A induces a type of equality of members of the set: a1 = a2 |

|

Groupoid

Groupoids are discussed on this page.

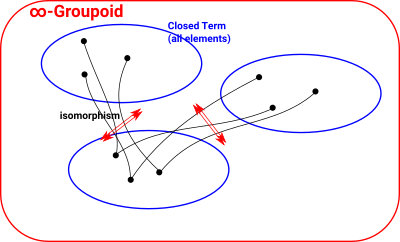

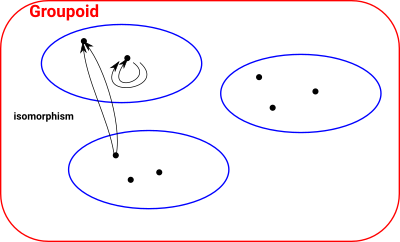

| A non-dependant type can be represented by a groupoid. |  |

| For a dependant type we need something more complicated, an ∞-groupoid. |  |

| There are multiple ways things can be equal. |  |

We can start to see how the type of equality discussed on this page has the structure of groupoids by looking at the examples on the page here.

Coding Groupoids

How could we implement these groupoids in computer code?

We need an inhabited type for each pair of terms that are equal but no type for pairs of terms that are not equal. Generating and using such a potentially large collection of types seems messy and not very workable. A family of types seems best implemented as dependant types but how can this be done for some pairs of terms but not others?

Simplical Sets

See page about simplical sets here.

Combinatorial Definition

A simplical set consists of a sequence of sets X0, X1 … and, for each n≥0, functions di : Xn->Xn-1 and si : Xn->Xn+1 for each i with 0≤i≤n such that:

- didj=dj-1di if i<j

- disj=sj-1di if i<j

- djsj=dj+1sj=id

- disj=sjdi-1 if i>j+1

- sisj=sj+1si if i≤j

Categorical Definition

Similar to combinatorial definition using order-preserving functions:

- Di : [n] ->[n+1]

- Si : [n+1] ->[n]